This quick story begins in the shadow of a bridge. With me in the shadows, there is a group of people who spoke of their working lives as though they had been displaced to its underside. They had survived corporate mergers, but not unscathed. Their lament was sharp; the “middle-management soup” of acquisitions had thickened into something unworkable. Too many managers, too many overlapping mandates, too much energy spent fighting one another rather than supporting the work. What might have been an integration was experienced instead as exile.

Their imagery was visceral; the workplace was likened to a gladiatorial arena, with managers locked in combat, climbing over bodies, and victories measured by survival rather than vision. In Bourdieu’s terms, a merger is a reshuffling of the field; symbolic, cultural, and social capital collide, and status must be renegotiated. However, the metaphor of gladiators suggests more than subtle manoeuvring. It evokes blood sport, where each advance requires another’s fall. The bridge connecting two organisational towers becomes less a passage of synergy and more a funnel into conflict, its stonework echoing with the clash of armour and ambition.

This struggle does not remain at the level of metaphor. It reshapes the workplace into a toxic environment. Staff turnover rises as exhaustion sets in, communication fractures under the weight of competing directives, and trust erodes. The damage spreads outward: customers pay both figuratively and literally, receiving diminished service at higher cost. Crucially, the burden is not distributed evenly. Intersectionality (Crenshaw 1989) reminds us that vulnerability is patterned. Women, migrants, casual staff, and younger employees absorb the contradictions most harshly. They are overseen by multiple managers with competing agendas, are monitored more closely, and are offered fewer protections. Mergers are rarely experienced as symmetrical.

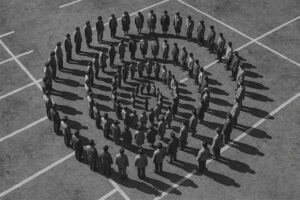

The bridge itself demands attention. A merger joins two houses, but a bridge is never neutral. Those with authority traverse it; those with capital remain elevated in their towers. Yet someone always ends up living beneath it, bearing the structure’s hidden weight. Douglas (1966) reminds us that societies preserve order by displacing mess, casting ambiguity into shadow. Under the bridge is where mess accumulates, the displaced, the redundant, the overlooked. It is a liminal zone, visible but unwanted, essential yet excluded. To live under the bridge is to embody the contradiction of being both inside and outside at once.

Philosophy sharpens the question. If bodies sustain the bridge, is integration itself ever ethical? Heidegger (1977) warns of enframing, the modern drive to treat beings as standing reserve, resources to be optimised. In merger logic, workers are no longer persons but “assets” to be rationalised. Yet rationalisation is selective: some are streamlined into leadership, others streamlined into precarity or redundancy. Intersectionality makes visible this patterning of risk: privilege cushions some, while difference magnifies exposure. The “synergy” celebrated in boardrooms becomes dispossession in offices, factories, and call centres.

Which returns us to the cryptic question offered by those in the shadows: “When two houses are joined by a bridge, who ends up living under it?” It is a question that resists easy resolution. It demands we look beneath the bridge to notice those carrying its load.

Note: Anthropology and philosophy, together, can do more than diagnose; they can also ask how bridges might be built otherwise. Not dismantled, perhaps, but redesigned so that those who bear their weight are neither invisible nor disposable.