This paper provides a glance at a future research project and a trend on social media. With empathy becoming the topic of the moment on social channels such as LinkedIn, it inspired a deeper look. In the past, I have looked at authenticity as a performance, and I could see some similarities. Empathy is becoming capital, something of neoliberal value to be traded, accrued, and generated profit from. In turn, empathy is being exposed as performative and even curated. I have applied some anthropological lenses, including those of Chronotopes.

Concept Draft:

Empathy is often described as an inherent human capacity, yet research across psychology, anthropology, history, leadership studies, and curatorial practice suggests that empathy is far from universal or evenly applied. Instead, it is selective, culturally patterned and shaped by power. This paper asks whether empathy should be understood not simply as an emotional response, but as a performative and curated practice that reflects broader structural, temporal and political conditions.

Psychological models have long distinguished between affective and cognitive empathy (Stein 1917/1989; Decety & Jackson 2004; Batson 2011), although recent work questions whether self-reported measures of cognitive empathy actually correspond to cognitive empathic ability (Murphy & Lilienfeld 2019). Leadership studies similarly reveal that empathy can operate along different routes, influencing relational and task-based performance in distinct ways (Kellett, Humphrey & Sleeth 2002). Phenomenological and anthropological scholarship expands this view by emphasising empathy as a relational and culturally situated achievement rather than an internalised skill (Hollan & Throop 2008; Hollan & Throop 2011; Throop & Zahavi 2020). What counts as empathy varies across societies and depends on moral frameworks, cultural scripts and the conditions under which one life becomes accessible to another.

Work in cultural memory, structural violence and necropolitics helps explain why empathy clusters unevenly.

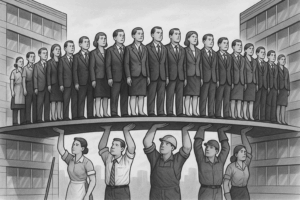

Some harms are dramatised, spectacular or narratively coherent, while others unfold slowly or bureaucratically and attract far less public concern (Galtung 1969; Nixon 2011). Processes of Othering (Said 1978; Spivak 1985) and state power (Mbembe 2003) determine whose suffering becomes recognisable, whose is minimised and whose lives are framed as grievable (Butler 2009). Historical studies of performance and re-enactment show that empathy can be actively produced through embodied storytelling and curated historical experience (De Groot 2011), while curatorial scholarship demonstrates how exhibitions and public narratives can be designed to elicit empathy in targeted ways (Mikhael 2018; Härtelova 2016).

To understand why empathy falters across difference, the paper introduces the chronotope (Bakhtin 1981) as a lens for examining how people inhabit divergent temporal worlds: linear, precarious, cyclical or intergenerational. Empathy often collapses when these time-worlds do not align, because the conditions shaping another person’s life are not legible within dominant cultural or narrative frameworks.

The aim of this paper is not to argue that empathy is insincere or wholly constructed, but to examine how it emerges through narrative, cultural practice and structure. By approaching empathy as curated, performed and shaped by temporal and political forces, the paper raises broader questions about how societies come to recognise some experiences while overlooking others, and what it might take to cultivate forms of empathy capable of engaging with diverse lifeworlds and structural realities.