Ben Stiller’s The Secret Life of Walter Mitty is often dismissed as a sentimental corporate self-help parable wrapped in Instagram-ready scenery. However, such reviews miss something more profound. Beneath its quiet protagonist and postcard aesthetics is a radical philosophical transformation, one that resonates strongly with Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch. Okay, I may be drawing a long bow here. Why not overanalyse one of my favourite films, so I thought I would skip the Hero’s Journey comparisons and think a little deeper. Is this film more than just a film about a man who learns to live a little? It is a narrative of rupture, of transvaluation, and of a life reclaimed from the machinery of meaninglessness.

The Übermensch: Not a Superhero, But a Breaker of Values

In Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the Übermensch (often translated as “Overman” or “Superman”) is not a superior being in the comic-book sense. Instead, it is someone who has transcended herd morality, created their values, and lives authentically in a world where traditional meaning, especially religious and moral absolutes, has collapsed.

The Übermensch arises after the death of God—a moment not of despair but of radical opportunity. In this godless world, one must become the source of meaning, not its servant.

Life Magazine is Dead. Long Live Walter.

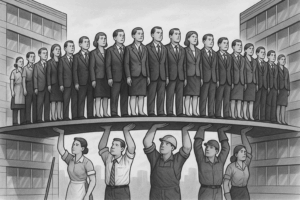

In Walter Mitty, the metaphorical “death of God” is the shutdown of Life magazine. Once a publication dedicated to visual storytelling and emotional truth, it is being dismantled by a sterile corporate regime. The new order speaks in bullet points and branding exercises. Meaning is being flattened into management-speak. Walter, a negative assets manager, is caught between the remnants of an old symbolic world (analogue photography, travel, mystery) and the cold logic of a digital future where everything is optimised, but nothing matters.

From Herd Animal to Creator of Meaning

Walter begins the film trapped in herd morality, conformist, passive, confined to daydreams. His fantasies are grandiose but safe: fighter pilot, Arctic explorer, daring rescuer. They are not actions but compensation for inaction. However, something breaks. He acts. He leaps, literally, onto a helicopter in Greenland. That moment marks the crossing of the threshold. From here, Walter is not imagining heroism. He is enacting it.

His journey—through Iceland, Afghanistan, and finally to the Himalayas—is more than geographical. It is spiritual, existential, and mythic. He goes in search of a photograph, but what he finds is far more profound: a life lived on his terms. This is not about “getting out of your comfort zone.” This is self-overcoming, Nietzsche’s core idea of willing oneself to become something new.

Transvaluation of Values

In Nietzsche’s terms, Walter enacts a transvaluation of values. He moves from a world where value is external (efficiency, productivity, compliance) to one where value is internal and embodied:

- He rejects the corporate contempt for the past.

- He reconnects with tactile experience, movement, risk, beauty.

- He lives Life’s slogan not as branding but as a personal credo:

- To see the world, things dangerous to come to, to see behind walls…

Crucially, Walter does not become a rebel or a destroyer. He does not blow up the office. He does something more radical: he stops needing it. He no longer depends on others for validation or meaning. He does not need his fantasies anymore, either.

In the Silence of the Sacred

There is a moment late in the film, quiet and often overlooked, that encapsulates this transformation. Walter finds Sean O’Connell (Sean Penn) on a Himalayan peak, photographing a snow leopard. The image is perfect, rare, and sacred. However, Sean does not take the shot.

“Sometimes,” he says, “I don’t. If I like a moment… I stay in it.”

This thought is not passivity; it is the rejection of instrumental logic. The refusal to reduce everything to proof, product, or outcome. This is the Übermensch’s stance: not to consume the sacred, but to dwell within it.

Walter returns home not as the man he was, nor as the hero he imagined, but as something else entirely, a being who no longer requires the old scaffolding of meaning.

Conclusion: A Myth for the Post-Meaning Age

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, for me, is not just a feel-good tale about adventure. It is a modern myth for a world that has lost its gods, be they divine or institutional. It suggests that in the ruins of those systems, one might still find a way not just to live but to become.

Walter Mitty does not escape his life. He reclaims it. In doing so, he becomes not a fantasy hero but something rarer: a creator of value, a man who has looked into the void and said, “I will make this matter.”

Moreover, that Nietzsche might say, is the beginning of the Übermensch.