Set in the river flats of Bacchus Marsh, the Mason’s Lane Sports Area is a familiar landmark: a patchwork of green ovals, athletics tracks, and playgrounds flanked by residential streets and fields of lettuce. However, this is not just a place for scheduled sports and school routines. This essay explores a seemingly mundane site of an informal dog park and how it can function as a rich ethnographic field site. It examines how human-animal relationships, informal social governance, and spatial routines generate what anthropologists would recognise as a form of more-than-human commons (Bresnihan 2015).

For many locals, especially dog owners, the space is something more subtle but no less significant: a place of daily ritual, connection, and movement. Each day, as the sun rises or sets, the trail circling the reserve fills with walkers, joggers and dog walkers. People of all ages stroll its crushed sandstone loop—some alone, some in pairs, and often with a dog or two. The track is an artery of the life of this space, where conversations are struck up, greetings are exchanged, and familiar faces nod. Down below, in the wide-open grassy spaces, dogs of all shapes and sizes tumble, race, sniff, and fetch, filling the reserve with motion and energy. At dusk the flashing LED collars dance around in the growing darkness.

At the heart of this shared rhythm is the old baseball diamond. Once built for a sport rarely played here, the diamond has evolved into something else entirely. Enclosed by a sturdy black chain-link fence—low on most sides, tall along the northern boundary—this quiet reserve corner has become an unofficial off-leash dog park. It is not marked on any map or sign, but everyone knows what it is.

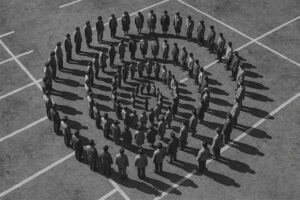

With four gates and plenty of open grass, it is a place where dogs can run freely and where their owners stroll along the fence line. Some, like myself, walk the outside perimeter, letting my anxious dog socialise at a comfortable distance. Others gather inside, forming loose constellations of companionship. This choreography of bodies—canine and human—unfolds not from official programming but from trust, familiarity, and tacit agreement. It is a space shaped by use, not design.

This is what anthropologist Włodarczyk (2021) might call a site of “more-than-human agency.” In her study of dog parks in Poland, she illustrates how urban environments are shaped through the entangled agency of humans and their canine companions. She argues that people often speak with their dogs, not merely for them. This framing challenges the traditional anthropocentric view of public space, instead inviting recognition of animals as active participants in co-creating meaning, routine, and place.

In Bacchus Marsh, this sense is palpable. Dog owners are not passive users of this space; they engage reflexively and responsively, shaping the landscape in tune with their dogs’ needs and behaviours. A dynamic commons has emerged through repetitive, negotiated practice—a dance of leash releases, play intervals, and social negotiations. These exchanges echo Marcel Mauss’s (1954) notion of gift economies—every bag of picked-up waste, every friendly reminder or shared ball, constitutes a minor social contract. In doing so, they generate and renew the bonds that make a commons thrive—not through market exchange or formal rules, but through mutual recognition and informal reciprocity. It is not governed by signage or regulations but by everyday micro-practices, spatial memory, and interspecies understanding.

Yet, just up the hill, a new chapter is being written. A $300,000 purpose-built dog park is currently under construction. Its features include a timber and tensioned chicken-wire fence, landscaped elements like tree branches, large rocks, crushed granite paths, and newly rolled turf coaxed into growth by diligent sprinklers. Soon, mass plantings and park furniture will follow.

While the new dog park signals investment and care, it raises questions. Will it match the rhythm and informality of the baseball diamond? Will it support the slow choreography of greetings over fences, the cautious introduction of nervous dogs, and the spontaneous chats that arise during a lap of the track? As some have noted on the associated Facebook group “It will be a nice landscaped garden, dog park not so much”. Some locals are concerned that this new space, while undoubtedly well-intentioned, may not reflect the actual dynamics of the community it aims to serve. Planning without ethnography risks designing for ideal users rather than real ones. Research has shown that successful shared spaces often emerge from the ground up, such as in the work of Matisoff and Noonan (2012). They require trust, not just turf.

After all, dog parks are not only about dogs. They are about people, too. They are about ageing residents establishing well-being rituals, newcomers locating themselves within a broader social fabric, and moments of trauma and healing negotiated through embodied, relational experience. In my own case, a once-frightened dog slowly rebuilt confidence through repeated, gentle exposure to others, facilitated by the semi-permeable safety of a chain-link fence and the unwritten etiquette of fellow walkers. From an anthropological perspective, these micro-interactions reflect broader cultural processes: practices of care, the negotiation of public intimacy, and the formation of what Victor Turner might call “communitas”—a shared, affective solidarity that arises from common experience in liminal spaces. Here, the dog park functions as a recreational site and a crucible of relational repair and quiet transformation.

What Bacchus Marsh has, in the quiet rhythms of Mason’s Lane, is not just an off-leash zone. It is a multispecies commons, a space co-authored by humans and animals, defined by movement, routine, and shared care. Concepts like more-than-human agency (Włodarczyk 2021) and communitas (Turner 1969) remind us that shared spaces are not only structured by policies or planning logic—they are lived into being through layered, everyday negotiations across species. Anthropology gives us the vocabulary and sensitivity to make such dynamics visible and valuable.

As urban design continues to evolve, may it listen to these gentle footprints in the grass.

Even a small-scale project like this dog park ethnography yields valuable insights. What seems like idle chatter on a park bench or dogs chasing tails is instructive for understanding how communities function. The ethnographic lens – immersive observation and thick description of everyday life – allows us to see the layers of meaning in these interactions. Geertz’s (1973) idea calls to mind that culture is a web of significance, spun by people themselves, which the anthropologist must interpret. Here, every leash ritual, every shared laugh over canine antics, is part of a local cultural text—a subtle performance of values, roles, and belonging.

Through it, I realised how a routine dog-walking circuit can reveal broader cultural patterns, not just etiquette and routine, but how community boundaries are drawn and maintained. Mary Douglas’s (1966) insight that ‘dirt is matter out of place’ resonates here: the rare appearance of an untrained or aggressive dog can momentarily disrupt the moral order, highlighting the otherwise invisible norms that govern this space. Notions of responsibility (Who cleans up? How do we gently enforce it?), practices of inclusion and exclusion (Which dogs or people feel welcome? Who might feel marginalised?), and the negotiation of shared space among diverse users. These are classic anthropological concerns, played out in microcosms daily at the dog park.

Anthropologically speaking, dog parks hold immense value as research sites. Unsurprisingly, so many scholarly papers, including anthropological ones, have been written about dog parks, especially during COVID-19, when dog parks were permissible. Researchers from various disciplines have noted that dog parks encourage exercise, build a sense of local community, and promote more humane attitudes toward pets (Lee et al. 2009; Glover et al. 2008).

Urban planners and geographers see dog parks as a positive feature of city life. They report how dog parks get people outdoors and interact, thus boosting social capital in neighbourhoods (Wood et al. 2005; Urbanik and Morgan 2013). Some have even suggested that dog parks are a step toward a more inclusive “zoöpolis,” an urban environment that integrates animal needs into human communities (Wolch and Rowe 1992). In other words, these humble fenced plots are recognised as ideal spaces for observing human-animal interaction, everyday social behaviour, and informal community dynamics on a broader scale. My journey through the diamond confirms these scholarly observations while adding a personal, ground-level perspective.

Participating in this everyday dog park world gave me insights that statistics or surveys alone might have missed – the tone of a morning gathering, the body language of dogs and owners in sync, and the unwritten etiquette everyone seems to absorb. Such details carry anthropological weight. They remind us that grand themes of culture and society are often woven into the most ordinary activities. Even in a small-town dog park, people negotiate rules, form alliances, display generosity, and perform identity. The ethnographic insight gleaned from “Walking the Diamond” thus illuminates how humans and dogs create a community that mirrors our innate desire to connect, belong, and find meaning in shared routines.

Reflecting on my time in Bacchus Marsh’s informal dog commons, I am struck by how profoundly this experience reaffirmed the value of ethnography—and, by extension, anthropology—in understanding everyday life. What began as simple walks with my canine companion evolved into a study of social cohesion and multispecies interaction.

It is no surprise that so many scholarly papers—including anthropological ones—have been written about dog parks. These sites are ethnographic goldmines, dense with human-animal interactions, space negotiations, informal governance, social performance, and community-making. They show how people live, relate, and create meaning in shared public spaces. I realised that no project is too small for ethnographic inquiry; even a local dog park, examined closely, can speak volumes about trust, cooperation, and community. It is little wonder that academics have gravitated to study dog parks because within these fenced enclosures are scenes that reflect society in miniature.

In the joyous chaos of dogs at play and owners in conversation, there lies a profound order—an unwritten social contract and a tapestry of relationships that enrich the community. Walking the park taught me that a dog park is never just a dog park; it is an everyday arena of human-animal co-creation, a stage where the bonds of society – between people and species – are continually woven, one toss of a tennis ball at a time.

A place where understands what the name “Raven” means.

References

Bresnihan P (2015) The more-than-human commons: From commons to commoning. In Space, power and the commons (pp. 93-112). Routledge.

Geertz C (1973) The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. New York: Basic Books.

Douglas M (1966) Purity and danger: An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Mauss M (1954) The gift: Forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies. London: Cohen & West.

Ostrom E (1990) Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Glover T, Parry D, & Shinew K (2008) Dog park users: An examination of perceived benefits of dog parks. Leisure Sciences, 30(1), 19–34.

Lee, H.-S., Shepley, M., & Huang, C.-S. (2009) Evaluation of off-leash dog parks in Texas and Florida: A study of use and perception. Landscape and Urban Planning, 92(3-4), 314–324.

Matisoff D, & Noonan D (2012) Managing the commons: The case of the Piedmont Park dog park. Proceedings of the 14th Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of the Commons.

Turner V (1969) The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. Chicago: Aldine.

Urbanik J & Morgan M (2013) A tale of tails: The place of dog parks in the urban imaginary. Geoforum, 44, 292–302.

Włodarczyk J (2021) My dog and I: We need the park – a more-than-human agency and the emergence of dog parks in Poland (2015–2020). Society Register, 5(3), 119–134.

Wolch J & Rowe S (1992) Companions in the park: A study of urban animal geography. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 10(6), 701–714.

Wood L, Giles-Corti B & Bulsara M (2005) The pet connection: Pets as a conduit for social capital? Social Science & Medicine, 61(6), 1159–1173.

Glover,T, Parry D & Shinew K (2008) Dog park users: An examination of perceived benefits of dog parks. Leisure Sciences, 30(1), 19–34.

Lee H, Shepley, M., & Huang, C.-S. (2009). Evaluation of off-leash dog parks in Texas and Florida: A study of use and perception. Landscape and Urban Planning, 92(3-4), 314–324.

Matisoff, D. C., & Noonan, D. S. (2012). Managing the commons: The case of the Piedmont Park dog park. Proceedings of the 14th Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of the Commons.

Turner, V. (1969). The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. Chicago: Aldine.

Urbanik, J., & Morgan, M. (2013). A tale of tails: The place of dog parks in the urban imaginary. Geoforum, 44, 292–302.

Włodarczyk, J. (2021). My dog and I: We need the park – more-than-human agency and the emergence of dog parks in Poland (2015–2020). Society Register, 5(3), 119–134.

Wolch J & Rowe S (1992) Companions in the park: A study of urban animal geography. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 10(6), 701–714.

Wood L, Giles-Corti B & Bulsara M (2005) The pet connection: Pets as a conduit for social capital? Social Science & Medicine, 61(6), 1159–1173.