I am passionate about midcentury architecture, furniture and fashion, plus a Robin Boyd fan-boy. Don’t get me started on Boyd-Baker house! What is upsetting is that in Melbourne, we are quietly losing an important piece of our history. In suburbs across the city, modest mid-20th-century homes – those low-slung midcentury modern dwellings with flat roofs, broad eaves and timber-lined interiors – are disappearing at an alarming rate.

Some are bulldozed outright; others are stripped of their character in the name of “renovation.” The ongoing loss of these homes, with little to no heritage protection to save them, has activists and heritage lovers sounding the alarm. Each demolished or “whitewashed” midcentury house is not just one less older home – it is the erasure of a cultural artefact, a small but significant chapter of Melbourne’s postwar identity.

Midcentury Marvels Under Threat

Drive through any Melbourne suburb and you might spot a demolition in progress sign where a 1950s or 60s home once stood. In recent years, even award-winning midcentury houses have met the wrecking ball. For example, Breedon House (built in 1966 in Brighton, and winner of a design award in its day) was razed in 2020 while awaiting a heritage assessment. Another modernist gem – a 1957 home at 17 Nautilus Street in bayside Beaumaris– was flattened to make way for a new build.

Without heritage protection, these design marvels are being knocked down to make way for new homes, often oversized, cheap and nasty mansions or townhouses that erase all trace of what stood before.

Local councils are theoretically responsible for listing and protecting significant properties, but many have slowly acknowledged the importance of midcentury homes. Heritage schemes are often outdated – some council studies from the 1980s and ’90s “didn’t even look at 20th-century architecture” – leaving this “golden age” of Australian home design largely off the radar. The result? A wave of postwar houses is paying the price, disappearing one by one.

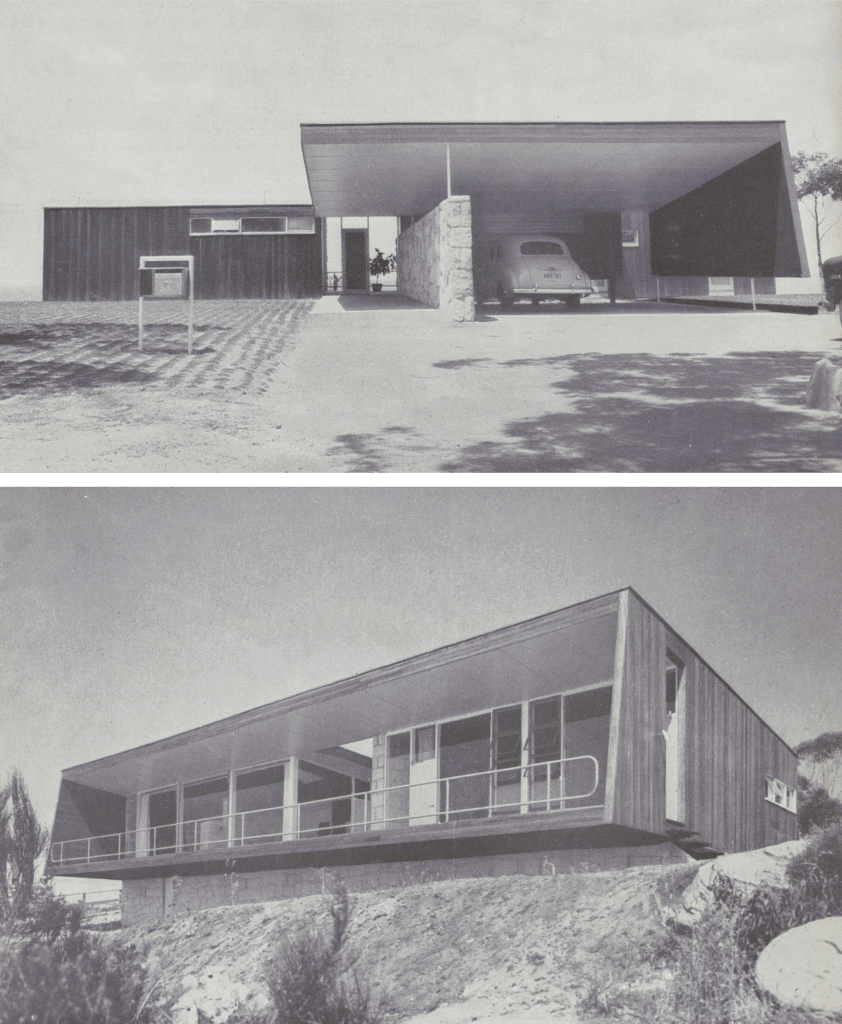

Photo from Trove: https://trove.nla.gov.au/blog/2024/12/13/place-call-home

Activists and architectural historians have watched this trend with growing concern. “All this shows just how precarious our heritage is “lamented one advocate when another 1960s home faced demolition in Beaumaris. Grassroots groups like Beaumaris Modern in the beachside suburbs have formed to lobby councils and raise awareness. “Only a handful [of these homes are protected]… we are way behind America on this,” says Fiona Austin, founder of Beaumaris Modern. Thanks to such pressure, a few councils have begun nominating midcentury houses for heritage overlays – but progress is slow and often too late. In one striking case, an architect-designed Brighton home was demolished while under review for heritage listing, after an interim protection order was denied because there was no “immediate threat”. The wreckers moved in, proving that the threat was all too real.

Even homes by Australia’s most celebrated architects have not been spared. In Beaumaris alone, “over the past 15 years… homes by well-known modernist architects such as Robin Boyd, Neil Clerehan and Roy Grounds have succumbed to demolition”. To lose works by Robin Boyd – the famed author of The Australian Ugliness and designer of elegantly simple modern homes – is especially chilling for architecture lovers. If Boyd’s houses are unsafe, what hope is there for the countless midcentury homes built by lesser-known architects or ordinary builders?

What Made These Homes Special?

Why all the fuss about “midcentury” design? For those unfamiliar, mid-20th-century homes, roughly late 1940s to 1970s, marked a radical shift from the ornate styles of earlier generations. These were the years of the Great Australian Dream: a modern home for the nuclear family in the booming postwar suburbs. Young architects and migrants fresh from war-torn Europe saw Australia as a blank canvas for new ideas. The result was a melting pot of influences that birthed a distinctly Australian version of modern architecture. Suburbs like Beaumaris, Balwyn and Caulfield became testing grounds for modernist innovation, and the average family home would never be the same again.

Midcentury modern homes broke away from boxy formal rooms and dark interiors. They introduced open-plan living, a fluid layout of lounge, dining and kitchen areas all connected – a novelty at the time. Large windows and glass sliding doors brought in natural light and blurred the line between indoors and outdoors. Architects prioritised large family living areas, indoor-outdoor flow, and artisanal features tailored to leisure and comfort. Instead of front verandahs and parlours, these homes opened onto patios, courtyards or back gardens, making outdoor space “as important as the indoor space,” as one midcentury homeowner observed. Many designs featured north-facing living rooms to capture winter sun, flat or skillion roofs (gently sloping roofs without the traditional pitch), and wide eaves to shade the summer heat. The aesthetic was clean and uncluttered, emphasising horizontal lines and low profiles that hugged the ground. It was modern and distinctly Australian, fitting our climate and casual lifestyle.

Midcentury house interiors embrace warm, natural materials. It is common to find timber panelling on walls or ceilings, from rich mahogany and teak to local hardwoods, bringing warmth and texture to living spaces. Built-in furniture was another hallmark of the era. Rather than fill a room with freestanding cupboards or shelves, architects often designed cabinetry, seating, and even bars built into the house’s structure.

These bespoke fixtures saved space and created a cohesive look – the house provided your bookcases, banquette bench, or cocktail bar in the lounge. In one famous 1957 modernist house in Beaumaris (nicknamed “the Eagle’s Nest”), the interior boasted “extensive interior wood panelling and a large fireplace” as focal points of a design that was hailed as “a beacon of mid-century modernity”. Many homes of the era also incorporated elements like feature stone walls, floating staircases, or decorative screens – touches of artistic flair integrated into the architecture.

In essence, these houses were total design packages. Every element, from the placement of the windows to the built-in dining nook, was considered part of a harmonious whole. They represented an optimistic time when Australians were experimenting with new designs and materials to create a better way of living. Not only architects, but also everyday homeowners (often newly arrived migrants or first-generation Australians) put their stamp on midcentury suburbia, blending modern ideas with personal touches. Waves of European migrants settling in Melbourne in the 1950s and ’60s brought a unique sense of style, leaving their mark on the look of our suburbs. Stroll down certain streets and you might see, for example, an Italian family’s 1960s home with Roman-style columns on the porch, or a Greek-Australian home with breeze-block screens and Mediterranean garden statues. Such details might seem quirky today, but speak volumes about the owners’ identities and aspirations.

(Photo suggestion: An interior of a well-preserved midcentury home – showing wood-panelled walls, a built-in sofa or bookshelf, and large windows opening to a garden. This helps readers visualise the cosy, integrated design elements.)

Whitewashing and “Updating” – Erasure from Within

Not all midcentury homes vanish in an instant cloud of dust; many are slowly erased through insensitive renovations. In real estate ads, we often see phrases like “updated for modern living” or “renovated in contemporary style” – code words for what preservationists call whitewashing. This often means painting over original materials with generic white paint or ripping out distinctive midcentury features to replace them with trendier fittings. The result might be a fresh white interior that photographs well for sale, but it also amounts to stripping the home of its soul.

Consider the timber-panelled walls and built-in joinery that once charmed these homes. In the current renovation frenzy, it is common for new owners to yank out 1960s built-in cabinets and seating, declaring them “outdated”, or to sand and paint over beautifully aged wood ceilings in flat white. Original brick fireplaces get dry-walled over or replaced with slick modern inserts; colourful vintage bathroom tiles are smashed out in favour of monochrome marble. One heritage architect noted that these homes’ modesty and simplicity have ironically made them a target – people assume they are plain or “ugly” and need a cosmetic overhaul. As Rohan Storey, a long-time National Trust advocate, put it: the broader community still does not accept modernist houses as “heritage”, with some dismissing them as “ugly, plain or ordinary”. This mindset leads to well-intentioned renovators effectively obliterating midcentury character in pursuing a “clean, modern” look.

Such changes may seem small in isolation – what is the harm in a coat of paint, after all? – But cumulatively, they amount to a quiet form of cultural vandalism. Painting over a mid-century timber feature wall might brighten the room, but it also whitewashes history (literally!). You are erasing the evidence of 1950s craftsmanship and material culture. Those timber walls and stone cladding were chosen to express a particular aesthetic of the time; to remove their surface is to muffle the voice of that era. Likewise, tearing out a built-in bar or banquette is not just a design choice, but a removal of a piece of the home’s story. It was common in the 60s and 70s for immigrant families to install built-in bars in their living rooms – a proud feature for entertaining guests in the new land. Younger Australians are now rediscovering these retro bars and banquette dining booths with affection, seeing them as charming relics of their grandparents’ generation. When we thoughtlessly junk these custom pieces, we lose the physical embodiments of midcentury social life – the cocktail hours, the family dinners, the “indoor-outdoor” parties that these houses were designed to host.

There is also a trend toward homogenisation that threatens midcentury homes. Drive through a neighbourhood where many older houses remain, and you will notice a troubling pattern: if a house has not been knocked down entirely, it has often been transformed to look like every other new renovation. Earthy brick exteriors are coated in dull grey render, timber window frames are replaced with black aluminium, and midcentury decorative screens are tossed in a skip. The unique spatial layouts get reconfigured – perhaps that once-open living-dining area is chopped up to create an extra bedroom, or a low-pitched roof is built into a two-storey addition that dwarfs the original. Bit by bit, the original design intent is lost under layers of “improvements.” An observer of Australian housing trends might wryly note that we are turning individual midcentury creations into cookie-cutter contemporaries.

It is worth noting that this phenomenon is not just happenstance – it reflects changing tastes and economic pressures. In today’s market, land values are high, and the fashion in interiors leans toward minimalist, white-on-white schemes. “Modern design’s insistent diktat that less is usually more” has led many to strip away ornament and colour in favour of a neutral palette. The problem is that less in this context often means less character, heritage, and storytelling. As one artist noted in a recent exhibition on migrant houses, we should not dismiss these original decor elements as “kitsch” or lowbrow; they have cultural meaning if we choose to see them. Unfortunately, the forces of gentrification and a rush to renovate mean many midcentury homes are either being demolished or renovated into oblivion before a new generation can appreciate them.

2022: https://www.realestate.com.au/sold/property-house-vic-balwyn-139337435

2025: https://www.realestate.com.au/property-house-vic-balwyn-148008064

Homes as Cultural Time Capsules

From an anthropological perspective, this loss is about far more than architecture. These midcentury houses are cultural time capsules. They embody the values, aspirations and everyday lives of a unique era in Australian history – roughly the 1950s to 1970s, when society was rapidly changing. When we wipe out these homes (or even their interior features), we delete physical evidence of who we were and how we lived. It is a material and cultural erasure that profoundly impacts our collective memory and urban identity.

Think of the postwar period: Australia welcomed immigrants from across Europe, young families sprawled into new suburbs, and the old British-oriented ways gave way to a new Australian modern identity. The houses of that era reflect that transition. Migrants, especially, imprinted their stories into their homes. As one design expert beautifully said, these houses were attempts “to build a place that reconciles the motherland’s loss with the fatherland’s adoption.” In other words, midcentury migrant homes were hybrids – part Australian modernism, part homage to the old country. They might feature Croatian pennants hanging in a sleek open-plan lounge, or Italian terrazzo tiles in a kitchen with locally made cabinetry. Every doily, brick facade, pebble garden and concrete cherub statue in those homes tells a story of cultural adaptation and pride. “They are all beautiful and deserve to be celebrating,” said Alex Kelly, an Australian of migrant heritage, speaking of the once-dismissed decor of his grandparents’ generation. These details might have been mocked as garish or unfashionable in years past, but today we recognise them as tangible heritage – the physical manifestation of multicultural Melbourne in mid-20th century.

When such a house is gutted or torn down, it is not just the loss of timber and brick. We lose a stage on which countless personal stories played out. Consider a midcentury living room in Footscray where a Vietnamese-Australian family celebrated their first Lunar New Year in Australia in the 1970s, or a Modernist home in Caulfield North where a Holocaust survivor family built a new life with a bold, light-filled design symbolising hope. These spaces witnessed important moments of ordinary people’s lives – birthdays, dinner parties, quiet afternoons, and frantic mornings. Anthropologists often say that buildings remember; they carry the imprints of social practices and rituals. When we obliterate the building, we also displace those memories. Future generations lose the chance to ever stumble upon them, to walk into a vintage 60s lounge and feel what life might have been like back then.

Urban identity suffers as well. Melbourne is a city that wears its history on its sleeve – or rather, in its streetscapes. We proudly preserve Victorian-era terraces and Art Deco apartment blocks, knowing they contribute to the city’s unique character. Midcentury architecture is an equally important layer of Melbourne’s identity, telling of a time when we grew into a cosmopolitan, modern city. The city’s visual and cultural tapestry becomes poorer if every midcentury building is replaced with generic new construction. We risk creating what one might call an architectural monoculture, where only the extremes of “old heritage” and glassy new developments remain, with nothing in between. The rich narrative of the postwar years – when Melbourne’s suburbs became incubators of innovation, when the Great Australian Dream took on a modernist flair – will fade from the landscape. As one National Trust executive warned, losing midcentury places means losing the physical proof of how Melbourne “embraced modernity” in the decades after WWII.

There is also a sustainability and continuity angle here. Destroying well-built older houses to build new ones is often an environmental negative, and it severs the continuity of place. Neighbourhoods like Beaumaris, Doncaster, or Heidelberg each have (or had) their midcentury flavour – a coherence of scale, material and style that makes them special. That character is a drawcard – it is no coincidence that photographers, film-makers, and mid-mod enthusiasts love areas with lots of midcentury homes. Wipe out those houses, and wipe out the vibe that made those suburbs distinctive. It is a loss not just felt by architecture buffs, but by anyone who values a sense of place in the city.

Protecting Our Midcentury Legacy

So what can be done to stop this quiet disappearance? Firstly, recognition is key. We must collectively recognise that midcentury architecture is heritage, even from our parents’ or grandparents’ lifetime, and not as obviously “historic” as a bluestone laneway. Thankfully, attitudes are slowly shifting. Heritage advocates, architects and community groups have been campaigning to have significant postwar buildings heritage-listed before they vanish. The Bayside council, for instance, has drawn up a list of 160 properties with midcentury modern features for potential protection. (This came only after earlier waves of demolitions caused public outcry.) There is pushback from some residents, who fear that heritage listing will affect property values or renovation plans, but others have embraced it. Architect and TV host Peter Maddison, who lives in a 1969 modernist home, welcomed the heritage overlay on his house, saying he feels like a custodian ensuring its survival for the future. This kind of stewardship mentality is precisely what is needed more broadly.

On a policy level, experts argue that all councils should update their heritage studies to include the 1940s-1970s period and proactively protect outstanding examples. The National Trust and other bodies have started programs to identify and advocate for midcentury “hidden gems” in various suburbs. Some success stories give hope: Lind House in Caulfield North, a 1950s modernist masterpiece by architect Anatol Kagan, was saved from redevelopment in 2017 after a public campaign, and is now lovingly restored by new owners. Each house saved sets a precedent that these places are worth keeping. However, relying on case-by-case, last-minute rescues is risky; we need a more systematic approach.

Beyond formal protection, there is a role for public education and celebration. The midcentury modern revival in popular culture (just think of the enthusiasm for Mad Men-era furniture and vintage decor) can be leveraged to show people the beauty of these homes in their original state. Open house events, local history tours, or online communities (such as the Modernist Australia website and Instagram accounts dedicated to retro homes) help turn the tide by making midcentury cool again, not just as a style to copy in new builds, but by cherishing the actual houses we still have. When younger buyers appreciate the charm of an untouched 1960s interior, they might choose to restore rather than rip out. Some are doing precisely that: in Melbourne’s north, a couple dubbed their 1970s fixer-upper “Shag Manor” and are restoring its shag carpet and funky features, rather than gutting it, as a tribute to the migrant family who built it. Such projects show that preserving midcentury elements can go hand-in-hand with living comfortably in the 21st century.

Finally, we can all engage in some activism in our way. If you are lucky enough to own or live in a midcentury place, consider yourself a caretaker of cultural heritage – keep those original elements if you can, and if you must change, do it sympathetically. If you are a neighbourhood resident, lend your voice when a notable local midcentury home comes under threat – write to the council, sign petitions, support groups like the National Trust or local historical societies. Even sharing before-and-after photos on social media of a beautifully preserved 60s home versus a characterless rebuild can raise awareness and perhaps inspire a change of heart in the next person about to pick up a sledgehammer.

Valuing the Story in the Structure

Heritage is not just about grand public buildings or 19th-century mansions but also about ordinary homes with extraordinary stories. Melbourne’s midcentury houses may look humble to some. However, they are laden with cultural significance: They reflect the optimism of the postwar years, the contributions of migrant communities, and the evolution of our domestic lives. To demolish or drastically alter them without thought is to disservice our city’s narrative.

In an activist spirit, we must stop treating midcentury homes as disposable. Each time we save a 1950s modernist dwelling or sensitively renovate a 1960s family home, we honour Melbourne’s cultural memory. These buildings are touchstones of who we have been – material memories in timber, brick and concrete. Instead of whitewashing them (literally or figuratively), let us celebrate their weathered clinker bricks, quirky built-in cupboards, and funky retro tiles. Let us see the beauty in what they represent. As the saying goes, they do not build them like they used to – and in the case of midcentury modern, that is true both technically and philosophically. We will never have that era again, but we can choose to keep its best pieces standing.

Melbourne’s identity is a patchwork of its past eras. By protecting midcentury architecture, we ensure the patchwork does not lose a whole panel. We keep the city layered and engaging, a place that embraces both history and modernity. In saving these homes, we are not just preserving old wood and glass – we are preserving a generation’s lived experiences and dreams, and passing those on to the next. It is a fight for memory against forgetfulness, for character against uniformity. Moreover, it is a fight every Melburnian who cares about our cultural landscape should join.

Injected with anthropological insight and a passion for preservation, this is a call to appreciate the midcentury marvels in our midst, before they vanish forever, taking a piece of us with them.

Sources:

- Samantha Landy, “Melbourne mid-century homes: Lax heritage schemes endangering important part of our history” – realestate.com.au

- Emily Hutchinson, “The fight to save mid-century marvels from the bulldozer” – realestate.com.au

- Andrea Nierhoff, “Melbourne bayside residents fight heritage listing of their mid-century modern homes” – ABC News.

- Balance Architecture (blog), “Modernism – Time to Protect Midcentury Modernism with Heritage Listing.”

- Mostafa Rachwani, “‘Doilies are beautiful’: Celebrating Australia’s mid-century migrant design” – The Guardian.

- Realestate.com.au interview with Fiona Austin, founder of Beaumaris Modern