An image circulating on LinkedIn dropped once again into my feed. I have seen many explorations of the issue. It depicts an area beneath a freeway overpass, and hundreds of jagged concrete spikes rise from the ground—not as an ornament but as a message. This space is not a place to stop, not a place to linger, not a place to exist unless you are in motion, respectable, and productive. You may have seen them in many public spaces like the Melbourne CBD or regional towns like Ballarat. Such installations—commonly known as hostile architecture—are a feature of contemporary cities that reveal more than they obscure. They are not merely pragmatic deterrents but instruments of social sorting. For anthropologists, they demand a closer reading—not as objects of design but as articulations of power embedded in space. Some quick thoughts on the subject:

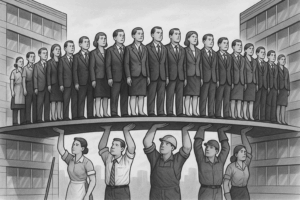

Anthropology reminds us that space is never neutral. It is produced, inhabited, contested, and policed. Michel Foucault (1977) argued that power is most effectively exercised not through overt repression but through the micro-architecture of control—through what he termed disciplinary mechanisms. The city becomes a site where bodies are sorted and behaviour regulated, not just by law but by layout. Henri Lefebvre (1991) similarly insisted that space must be understood as a social product. It is not just the container of action but the outcome of political, economic, and cultural forces. Hostile design elements such as anti-homeless spikes or segregated seating arrangements exemplify conceived space: a vision of the city produced by those in power and planners in which certain presences—particularly those of the unhoused, unemployed, youth, or otherwise marginal—are systematically hidden, or more to the point erased.

The Conditional Right to the City

In Lefebvre’s formulation of the right to the city, the urban is envisioned as a space co-produced by its inhabitants—a shared commons in which participation is a right, not a privilege. However, this vision has increasingly given way to a neoliberal logic of spatial management. As David Harvey (2008) notes, the right to the city is now reserved mainly for those who contribute to its commodified value. Under this regime, public space is reshaped to prioritise efficiency, consumption, and surveillance. Individuals who do not conform to respectability or economic productivity norms—those who cannot ‘pay their way’ — are treated as spatial contaminants. Setha Low (2001) observed how urban design has become a method of exclusion through aesthetic rationality. Spaces appear open yet are silently coded against the poor, the racialised, or the idle. Hostile architecture is not a bug of modern urbanism but a feature.

The Spatialisation of Othering

This sorting is not only physical; it is symbolic. Drawing on Edward Said’s (1978) notion of Othering, we can see how architectural interventions reinforce narratives of undesirability and deviance. Concrete spikes do not merely prevent sleeping—they designate sleepers as threats. In material form, they enact the idea that some bodies are out of place. Ananya Roy (2003) critiques how planning discourse frames informal use of space—such as street vending or public sleeping—as unlawful, even as it relies on informal communities’ labour and cultural contributions. The same people who sustain urban life are denied visibility or safety within it.

Insurgent Occupations and Everyday Resistance

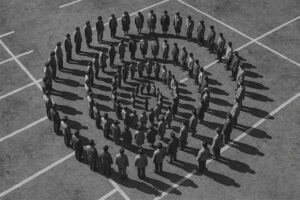

However, cities are never wholly under control. James Holston (2008) describes how marginalised groups assert their presence through what he calls insurgent citizenship: practices that challenge normative claims to urban space and make demands from the margins. These practices range from large-scale protests and encampments to quieter gestures of endurance and creativity. AbdouMaliq Simone (2004) has shown that the urban poor often create functional infrastructures through informal cooperation. These infrastructures are not only material but also social—spaces of care, kinship, and persistence in the face of engineered exclusion.

Reading the City Anthropologically

To view the city anthropologically means attending not only to its buildings and streets but also to the moral economies and ideological structures they express. Spikes beneath an overpass are not just deterrents but spatial verdicts about who belongs, who threatens, and who must remain unseen. Such verdicts are not permanent. However, they require contestation—not only by architects and activists but also scholars willing to trace the entangled lives of infrastructure and inequality. Anthropology, in this context, offers both a diagnostic and an ethic. It invites us to read the city against the grain, reveal its hierarchies, and reimagine it not as a marketplace but as a common world-in-the-making.

Reflection

Despite many of the crude remarks from those who have consumed the point of view of hegemonic powers, discourse is happening. Becoming aware of the the little metal slugs embedded in to stone window sills, oddly shaped seating, textured surfaces is a beginning. Instead of addressing the underlying issues that results in rough sleepers or homelessness, many forms of violence are committed to those living with in a places boundaries. Resolve those issues humanely to avoid aggressive and violent architecture .

References

- Foucault M (1977) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Penguin.

- Harvey D. (2008). The right to the city. New Left Review, 53, 23–40.

- Holston J (2008). Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil. Princeton University Press.

- Lefebvre H (1991). The Production of Space. Blackwell.

- Low S (2001). The edge and the center: Gated communities and the discourse of urban fear. American Anthropologist, 103(1), 45–58.

- Roy A (2003). Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71(2), 147–158.

- Said E (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

- Simone A (2004) People as infrastructure: Intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Public Culture, 16(3), 407–429.