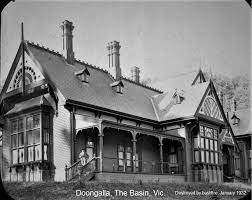

Like my father, I attended The Basin Primary School in Melbourne’s far east. Nestled at the foot of Corhanwarrabul (Mt Dandenong). An amazing place to grow up, BMX bike riding through the bush, creeks to explore, and looming summer threats of bushfire. The primary school had four ‘houses’ named after local settler homes: Miller, Chandler, Ferndale and my house, Doongalla. I have vague memories of what we were told about each house, one thing I remember was the Doongalla Estate being destroyed in the Black Friday.

In later years, we would venture up to the site where only retaining walls and a set of steps remain. Remnants of the garden, like old European trees, still survived. The open space cut into the bush also had a vista over Naam (Melbourne). In the 1980s, there was no mention of the house’s name coming from the original custodians of the land, the Wurundjeri and Bunurong people of the Kulin Nation. The whitewashed history of the area is likely where my interest in place heritage was born. So, 40 years later, I can reflect differently on Doongalla Estate and its relationship with the community. This is what I have discovered so far.

The Doongalla Forest Reserve of 279 hectares, situated on the western slopes of Mt Dandenong, now occupies land once selected between 1885 and 1893 by Samuel Collier, J. Barnes, J. Jackson and the Bruce brothers. The estate reaches from 152m to 268m above sea level, topping out at Mt Corhanwarrabul (also known as Burke’s Lookout). In 1889, the Bruce brothers erected a Swiss-style chalet on land purchased from Collier. That property was acquired in 1891 by Sir Matthew Davies, who also bought the surrounding lots. Following flood damage to the original chalet, Davies demolished it and in 1892 constructed a new mansion—originally named “Invermay”—at an estimated cost of £35,000. Materials were hauled up Kerrs Lane (now Pig Lane) by tramway using horses and bullocks.

The new house, consisting of 32 rooms including cellars, servant quarters, and stables, was lavish in both design and detail. It featured a central courtyard and was built with high-quality Croydon bricks, slate roofing, exposed Oregon beams, and panelling in Kauri, silky oak, and Blackwood. One room was decorated with French tiles screwed into timber boards. A swimming pool fed by a nearby creek added to the estate’s luxury. Doongalla became known as a weekend haven for Melbourne’s wealthy. Guests enjoyed house parties, fine food, wine, and even moonlit swims. Recitations by Harry Chandler were a social highlight. Sir Matthew Davies was a significant figure in Victoria’s land boom era, creating a complex web of over 30 companies to speculate in land. His empire collapsed during the 1890s economic crash, leaving him bankrupt with £250,000 in debts. The Bank of New South Wales took over Doongalla and installed a caretaker.

In 1908, the estate was purchased by Miss Helen Simson of Toorak, who renamed it Doongalla—a contraction of the Aboriginal term “Doutta Galla,” often interpreted as “Place of Peace.” The name also refers to Dutigalla, wife of Jika Jika, a figure in early Melbourne colonial records. Under Simson’s ownership, extensive renovations took place, including building new staff quarters, fencing, elaborate gardens, and infrastructure upgrades such as a water scheme and electricity. Miss Simson employed workers at high wages and supported local infrastructure and community projects. She died in 1912, and her 15-year-old niece inherited the estate, managed by her father L.K.S. McKinnon, a prominent racing identity. After the niece’s death in 1922, the estate passed to T.M. Burke, who envisioned a golf course and donated land for Burke’s Lookout.

In 1932, fire swept toward the estate. Despite good clearance and a water supply, a windborne ember likely ignited the roof. Locals, including Fergus Chandler and the Dobson family, attempted to fight the fire but were forced to watch the mansion burn. Only the servant quarters and 13 chimneys remained. From 1934, parts of the land were sold and subdivided. The remaining 279 hectares were sold to the Smith Brothers in 1935, who established a timber mill. A controversial Forest Commission pamphlet once blamed the brothers for environmental degradation, but this was later retracted after Roy Smith demanded an apology. Ownership changed again in 1940, and in the 1950s the Victorian Government acquired the land following conservation campaigns, particularly one led by Sir Gilbert Chandler. The stables were later demolished, but the servant quarters remain in use by the park warden.

Today, the former site of the mansion features picnic areas, lawn terraces, garden remnants, and interpretive tracks such as the Collier Walk, Chandler Walk, and Lawrence Walk—each commemorating early settlers and local figures. The name “Doongalla” is thought to derive from an Aboriginal word, possibly meaning “close to water” or alluding to the mist-shrouded landscape typical of the Dandenong Ranges. While the exact linguistic origins remain unclear, the choice of name underscores the common 19th-century practice of drawing on Indigenous languages to evoke a romanticised vision of the Australian landscape, often without proper attribution or understanding of cultural significance.

This superficial borrowing of language without consultation or understanding contributes to a broader pattern of cultural erasure. While settlers named their estates with Aboriginal words, the lives, knowledge systems, and presence of the First Nations peoples who had stewarded those landscapes for tens of thousands of years were marginalised and obscured. The Doongalla Estate, like many colonial properties, sits atop a deeper cultural landscape—one shaped by the Wurundjeri and Bunurong people, who maintained intricate relationships with the land through seasonal knowledge, fire management practices, and spiritual connection. This land was never ceded.

Today, the Doongalla Forest Reserve, now part of the Dandenong Ranges National Park, remains a favourite destination for hikers and history enthusiasts. Traces of the estate—such as exotic trees not native to the region, old garden beds, stone retaining walls, and staircases—emerge subtly from the undergrowth, reminders of an era when colonial wealth carved stately homes into the landscape. The area’s walking tracks, such as the Doongalla Homestead Site Track and the Fireline Track, offer natural beauty and a contemplative connection to the site’s layered past. Interpretive signage gives visitors glimpses into the estate’s story, fostering an appreciation for the fragility of built heritage and natural ecosystems in fire-prone landscapes.

While the mansion is gone, Doongalla’s legacy endures in the memories embedded in the land—a story of ambition, collapse, recreation, and resilience etched into the forested hills of the Dandenongs. Yet within that legacy is an opportunity to confront and reframe history: to acknowledge the silences in the colonial record, to respect the enduring custodianship of the Wurundjeri and Bunurong peoples, and to imagine how landscapes like this might hold space for multiple, interwoven narratives of belonging and memory.

For me, it is a point of reflection of memories of place within my own life. The area is my place, my Country, where stories and experiences shape who I am today. I lived metres away from the Miller’s Homestead, which had a similar colonial settler history. I really do regret that I grew up in an era that was still neglecting First Nations history, especially in such a rich environment. All I can do now is try to discover some of that history myself. Doongalla and its stories can help do that by linking my cultural heritage to those who first took care of the space. But we must be open to hearing the harmful, even horror, stories that it may reveal.