A Personal Turning Point

A couple of months ago, I hit a young male kangaroo at 90 km/h on the Diggers Rest–Coimadai Road. It was a pitch-black night. In that moment, I realised what had happened, and the weight of it struck me, literally and emotionally. I’ve always enjoyed seeing kangaroos, even just on the side of the road, and I’ve long made a point of driving carefully at dawn and dusk when they are most active. But that night, I wasn’t as considerate as I should have been.

At the posted 100 km/h speed limit, I had no time to react. I keep asking myself: if I had been travelling at 80 or 70, would I have avoided him? Maybe. That question has lingered with me, questioning if I was in “right-relations” with Kangaroos, or any other wildlife. This question has sharpened my perspective on how we, as a community, treat kangaroos in Moorabool, which is situated across the traditional lands of Woi Wurrung, Wadawurrung, and Dja Dja Wurrung.

The Language of “Harvest”

Not long after, I learned that Moorabool Shire’s environmental strategy is being developed, and that the state’s Kangaroo Harvesting Program continues to operate in the area. The language of “harvest” struck me immediately. It suggests a crop to be collected, a resource to be extracted. Kangaroos are reduced to “stocks” measured in quotas and commercial returns.

Let’s be clear: “harvest” is not stewardship; it is commoditisation. It reframes a sentient being as an economic unit. Call it what it is: a cull. The shift in language is not neutral, it makes killing palatable by dressing it up as “sustainable use.” It avoids more complex questions about how we design roads, plan housing, or manage landscapes in ways that continually put kangaroos at odds with us.

A Human-Centred Hegemony

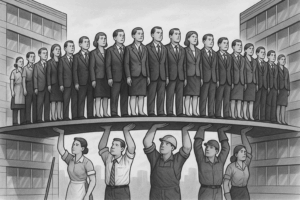

This is part of a larger hegemony in how we think about the environment: human needs are always placed at the centre, and everything else is managed around us. Agriculture, development, and infrastructure are considered non-negotiable. Wildlife are expected to adapt, or else be “controlled.”

But this is a flawed starting point. It produces contradictions: we talk about sustainability, liveability, and climate resilience, but we allow the ongoing displacement and killing of the very beings who embody ecological health. Our planning documents praise “connectivity” and “biodiversity,” yet kangaroos are absent from the picture, or worse, turned into statistics in a quota.

First Nations Perspectives

There is another way. First Nations knowledge tells us that kangaroos are not “stocks” but kin, custodians, teachers, and co-inhabitants of Country. I cannot speak for First Nations people, nor do I claim their authority, but what I have learned in recent years has been deeply insightful.

First Nations ways of knowing are not sentimental; they are grounded in long-standing observation and relational ethics. They show that coexistence is possible when humans exercise restraint, rather than when animals are forced to adapt to human expansion. If Moorabool wants to lead, it should embed this knowledge in its policies, not as a token consultation, but as genuine guidance on how to care for Country.

Sadly, Moorabool has a poor record of recognising First Nations people, past, present, and likely future. That makes this moment even more important. The development of a new environmental strategy presents an opportunity to shift direction.

A Council at the Crossroads

Council and government policy makers now face a choice. They can continue reinforcing human-centred management, hiding behind the language of “harvest” while ignoring the contradictions. Or they can take a different path: one that recognises kangaroos as rightful co-inhabitants of the Shire, and makes their protection central to caring for Country.

A strategy that embraces coexistence would not only be more honest, it would align with the lived experiences of many residents. My own roadside encounter is just one story. Others in Moorabool have also been jolted into reflection, whether through close calls, the sadness of roadkill, or the simple joy of seeing kangaroos grazing at dawn. These experiences connect us to the animals around us, reminding us that sustainability is not an abstract concept. It is lived.

Why It Matters

The tragic deaths of two young nurses while helping an injured kangaroo remind us how deeply Victorians value these animals, and how fraught our relationship with them has become. Kangaroos are not obstacles to be managed, nor statistics in a spreadsheet. They are part of the living fabric of this place.

If Moorabool’s strategy is to mean anything, it must confront the hard questions: How important are kangaroos—and all native animals—in shaping a healthy, respectful culture? What would it mean to design our planning, roads, and policies not just for human convenience, but for coexistence?

The answers to these questions will determine whether Moorabool chooses to perpetuate a system of commodification or takes the lead in building a future of genuine environmental stewardship.