In Australia, a performance ritual that feels timeless and meticulously rehearsed is conducted each April. The solemnity of the ANZAC Day dawn service call back to a military campaign over a hundred years ago. Today, it resonates through a contemporary landscape of social media hashtags, sporting events, and civic performances. It is a national memory in motion—recurring, refracted, and reassembled.

In this essay, I explore ANZAC not as a fixed historical truth but as a mythology in loop—a narrative system that generates authenticity through repetition, performance, and recognition. Drawing from anthropological theories of authenticity, digital cadence, and social memory, I argue that ANZAC operates as a dynamic cultural mechanism that affirms national identity while selectively structuring whose memories matter.

This essay is not a critique of ANZAC as false or fabricated; it is a brief investigation into how authenticity is constructed and maintained in a mythology that must continuously adapt to remain resonant. It is a myth that performs national unity through a shared past, even as it is mobilised to legitimise contemporary politics, identity claims, and institutional values.

As a mythology, ANZAC functions through temporal, emotional, and symbolic loops. These loops allow layering personal family memory, institutional ritual, and mediated spectacle. However, they also raise important anthropological questions: What makes a national narrative feel authentic? Whose stories are repeated and elevated, and whose are silenced or obscured? How do digital spaces alter the rhythms and reach of remembrance? What follows is not a linear history of ANZAC but an exploration of its cultural cadence: how the myth travels through time, space, and media, looping back each year to reaffirm a sense of who we are—and to quietly shape who we are allowed to be.

The Performative Nature of National Authenticity

Authenticity is often assumed to be intrinsic—something that can be possessed or lost. However, as scholar Richard Handler argues, authenticity is not a quality of the object or subject itself but rather a social judgement, an act of recognition grounded in cultural expectations (Handler 1986). In the context of national mythologies like ANZAC, authenticity is not simply discovered in the past; it is performed in the present.

The ANZAC tradition, anchored in the Gallipoli campaign of 1915, has long been heralded as the birth of the Australian national character: mateship, courage under fire, irreverent humour, and egalitarian sacrifice. These traits are routinely presented as “authentic” expressions of the Australian spirit. However, the continued relevance of this narrative lies not in its historical exactness but in its ritualised repetition—in the ways it is embodied, enacted, and emotionally affirmed each year through commemorative practice.

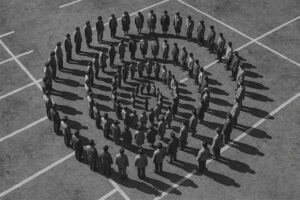

From school assemblies to dawn services and televised documentaries to Anzac-themed AFL matches, the mythology is performed across a wide social field. These performances do more than remember the dead; they reaffirm a national self-image. In doing so, they create what Charles Taylor calls a “social imaginary”—a shared sense of belonging constantly reinforced by narrative, practice, and affect (Taylor 2004).

However, these performances are never neutral. Like all rituals, they are structured by power. What gets included as “authentically” ANZAC—and, by extension, “authentically” Australian—is often shaped by dominant cultural scripts. For decades, this meant a focus on white male soldiers from Anglo-Celtic backgrounds. More recently, the commemorative discourse has expanded to include Indigenous soldiers, nurses, and migrant communities, but these inclusions still operate within the constraints of what is culturally legible as ANZAC.

Thus, national authenticity is not a mirror—it is a stage. Moreover, not all bodies and histories are equally visible at this stage.

Digital Cadence and the Re-Mediation of ANZAC

In recent decades, ANZAC mythology has expanded and transformed—most notably through its migration into digital space. As Australia’s commemorative practices adapt to a digital society, the rhythms of remembrance shift. Memory no longer belongs solely to formal institutions; it is shaped and circulated by individuals, families, influencers, and algorithms. Here, the concept of digital cadence—the temporal flow and pacing of cultural content online—becomes a useful anthropological tool.

Each year, the ANZAC myth is reactivated on social media platforms, creating synchronised pulses of national reflection. These pulses are not spontaneous but patterned, curated, and accelerated by digital infrastructures. Users post family photos of war veterans, share stylised images of poppies and flags, or quote the “Ode of Remembrance” with hashtags like #LestWeForget or #ANZACDay. In doing so, they participate in what anthropologist Daniel Miller describes as the domestication of the digital: integrating national identity performance into the texture of everyday online life (Miller et al. 2016).

However, the digital also fragments the loop. The solemnity of commemoration can sit awkwardly alongside advertising for Anzac Day sales, memes, or performative virtue-signaling. This blurring of commercial, sacred, and personal registers opens space for plural expression and cultural tension. The digital environment thus complicates the question of what constitutes an “authentic” ANZAC memory. Is it a heartfelt Facebook post about a grandfather’s service? A TikTok reenactment of Gallipoli? An Instagram tribute with a branded watermark?

Moreover, digital platforms invite counter-narratives into the loop. Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander soldiers—long excluded from official histories—now find visibility through grassroots digital activism. These interventions not only enrich the mythology but challenge its selective silences. They demand space within the loop, insisting that remembrance must be national and just.

Still, inclusion is not always empowerment. Representation within the ANZAC myth can risk absorbing difference into sameness—flattening cultural specificity into a universalised ideal of sacrifice. As the loop expands, the challenge becomes recognising multiplicity without collapsing it into a single narrative of belonging.

Inclusion, Exclusion, and the Politics of Memory

National myths are powerful not only because of what they remember but also because of what they allow us to forget. The ANZAC mythology, as both a cultural loop and a mnemonic performance, operates through selective remembrance. It draws a bright spotlight on particular forms of sacrifice and service while others remain in shadow. In this way, mythology is not just a story of the past—it is a mechanism of social sorting.

In recent years, efforts to broaden ANZAC commemorations have led to the inclusion of once-marginalised participants: Indigenous soldiers, women, nurses, migrants, and even civilian war workers. These moves are often framed as corrections to a historically narrow vision of national service. However, they also reveal the conditions under which inclusion becomes possible. To be remembered within the ANZAC narrative, one must conform—implicitly or explicitly—to its symbolic values: bravery, duty, and loyalty to the nation.

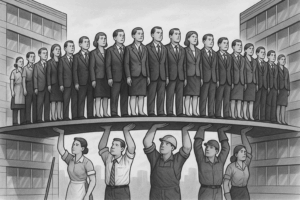

Ghassan Hage (1998) describes nationalism as a form of governmentality—a structure of belonging that defines not just who is “in,” but who gets to imagine themselves as legitimately Australian. Within the ANZAC loop, this logic plays out subtly. For example:

- An Australian First Nations soldier may be celebrated for their military service but not for their political resistance to colonisation.

- A nurse’s wartime labour may be honoured while her postwar domestic struggles are suppressed.

- A migrant’s service in Vietnam might be recognised, but their family’s refugee story remains culturally illegible.

In this way, inclusion can function as aesthetic pluralism—a recognition of difference that still conforms to dominant frames of worth. What looks like diversity may mask deeper structural exclusions.

This raises important anthropological questions about the politics of memory:

- Whose grief is grievable in the national imaginary?

- Who is allowed to be heroic—and on what terms?

- What kinds of lives are deemed worthy of commemoration, and what kinds of deaths are silenced?

These are not abstract concerns. They shape public funding, education curricula, museum exhibitions, and the moral vocabularies of national identity. In an era where Australia is grappling with its colonial past and multicultural present, the mythology of ANZAC risks stabilising a version of history that is legible but incomplete.

Digital Heritage and the Inclusion of Silenced Voices

The digital preservation of ANZAC heritage has recently allowed some previously marginalised voices to be heard and recognised beyond official historical narratives. These initiatives do not simply diversify the commemorative field; they challenge the cultural legibility of the ANZAC myth and expand its mnemonic loop.

For First Nations veterans, digital oral history projects such as Serving Our Country have profoundly contributed to national memory. By travelling across communities to record the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander servicemen and women, these projects have enabled a reframing of war memory that centres Indigenous voices (Beaumont and Cadzow 2018). These interviews—archived and curated in digital repositories—are acts of preservation and justice.

Institutions like the Australian War Memorial have also contributed to this shift. Through its digitised collections and the For Our Country memorial, the AWM now hosts searchable archives of Indigenous service histories, often enhanced by photographs, letters, and community-submitted biographies (Australian War Memorial 2015).

Similar efforts have brought visibility to Chinese-Australian diggers, whose loyalty and sacrifice have long been occluded by the whiteness of ANZAC iconography. The Chinese ANZACs initiative by the Department of Veterans Affairs uses short online documentaries and interactive storytelling to recover their histories (Clyne and Smith 2015).

The same digital curation has allowed for a deeper representation of women’s wartime labour. Projects such as the Australian Women in War digital series and Women in the Second World War: In Their Own Words allow nurses, munitions workers, and servicewomen to speak in their own voices—through digitised letters, diaries, and recorded interviews (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019; 2020).

Spaces like the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne, where interactive screens now feature recorded veteran testimonies—including women and Indigenous Australians—exemplify this shift in practice (Saliba, Young and Ayres, 2021). Anthropologically, these changes represent a movement toward plural memory-making—a form of national myth that affirms difference as central to identity, not marginal to it (Waterton, Sumartojo and Drozdzewski, 2021).

Toward a Plural Heritage Future

If ANZAC mythology is a loop—repeating, adapting, and reaffirming a national story—it must now reckon with its contours, not to erase its power but to widen the circle of remembrance. The challenge is not whether ANZAC is still relevant but to whom, how, and at what cost.

In this context, authenticity is not about preserving a myth in amber. It is about asking: What makes this story feel true? Moreover, what truths are left untold to make it so? As Australia grapples with its colonial foundations, shifting demography, and contested histories, the task ahead is not simply to diversify the faces in the story—but to transform the grammar of the myth itself.

This means recognising ANZAC not as a closed canon but as a dynamic cultural framework—a living inheritance that must be constantly re-evaluated through ethical, historical, and anthropological scrutiny. In practical terms, it may mean:

- Institutional support for underrepresented voices and stories—not as appendices to the national narrative but as integral to it.

- Community-led commemorations that challenge top-down structures of heritage and allow memory to be local, intimate, and dissenting.

- Digital platforms that do more than aestheticise remembrance, instead becoming tools for participatory historiography and contested memory work.

- Educational reforms that treat ANZAC as a gateway to complexity—not just pride, but also trauma, absence, and multiplicity.

Such shifts demand a willingness to move beyond performative pluralism toward a reflexive heritage practice that does not just ask who is being remembered but who is doing the remembering and why.

To embrace a plural heritage future is not to reject the ANZAC myth but to ask it to do more. To carry the weight of national pride and the burdens of silence. To reflect not just a single legacy but a constellation of intersecting histories—some tragic, some heroic, some yet to be fully known.

In the loop of national memory, authenticity does not mean sameness. It means honesty. Perhaps the most authentic gesture we can make now is to ask better questions—of ourselves, our past, and the stories we choose to tell in its name.

Final Thought

In 1914, Australia had a population of just below five million people. Today, it exceeds twenty-seven million. The situation involves more than just population growth; it represents a fundamental change in the nation’s social structure and cultural and political makeup. The ANZAC mythology created during a different era in Australia continues in today’s society and features deep diversity and historical reflection. The memory loops must broaden as our population grows and becomes more diverse to accommodate additional voices and truths. ANZAC mythology can stay relevant only if it represents today’s Australia that remembers its history rather than merely the past version of the country.

References

Australian War Memorial (AWM), 2015. Researching Indigenous Service. [online] Canberra: AWM. Available at: https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/indigenous [Accessed 25 Apr. 2025].

Beaumont, J. and Cadzow, A., 2018. Serving Our Country: Indigenous Australians, War, Defence and Citizenship. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing.

Clyne, J. and Smith, R., 2015. Chinese Anzacs. Canberra: Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA), 2019. Australian Women in War: Investigating the Experiences and Changing Roles of Australian Women in War and Peace Operations 1899–Today. Canberra: Australian Government.

Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA), 2020. Women in the Second World War: In Their Own Words. [online] Canberra: Australian Government. Available at: https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/resources/women-second-world-war-their-own-words [Accessed 25 Apr. 2025].

Drozdzewski, D., 2016. Does ANZAC sit comfortably within Australia’s multiculturalism? Australian Geographer, 47(1), pp.3–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2015.1108700

Drozdzewski, D. and Waterton, E., 2016. In remembering ANZAC Day, what do we forget? The Conversation, [online] 20 Apr. Available at: https://theconversation.com/in-remembering-anzac-day-what-do-we-forget-58132 [Accessed 25 Apr. 2025].

Handler, R., 1986. Authenticity. Anthropology Today, 2(1), pp.2–4.

Hage, G., 1998. White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society. Sydney: Pluto Press.

Miller, D., Sinanan, J., et al., 2016. How the World Changed Social Media. London: UCL Press.

Saliba, S., Young, W. and Ayres, M., 2021. Teaching memory: digital interpretation at the Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne. Architectural Theory Review, 25(1), pp.56–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13264826.2021.1913437

Taylor, C., 2004. Modern Social Imaginaries. Durham: Duke University Press.

Waterton, E., Sumartojo, S. and Drozdzewski, D., 2021. Encounters with ANZAC in a digital world: tropes and symbols, spectacle and staging. In: D. Drozdzewski, S. Waterton and E. Sumartojo, eds. Geographies of Commemoration in a Digital World: ANZAC @ 100. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.55–79.