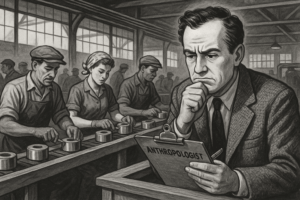

An architectural anthropology of everyday infrastructure

At first glance, these twin red-brick houses evoke uniformity (see blow) — repetition, symmetry, state logic. But a closer look reveals a very different story: variation within standardisation, adaptation within constraint. This image is more than a record of architecture; it is a portrait of lived negotiation — an anthropology of the ordinary.

The mirrored design of the homes, a hallmark of late 20th-century social housing in Australia, speaks to bureaucratic goals: affordability, efficiency, durability. Yet these “standard templates” belie the rich variation of everyday life unfolding inside and around them. In architectural anthropology, such designs are often viewed as technologies of containment — not just spatial but social. They reflect a state-led vision of domesticity: minimal, replicable, neutral. But people do not live neutral lives.

Look closely. The air conditioning units shoved through windows, the cardboard patch in the pane, the mismatched fences, and the absence of a tended garden are all subtle interventions — or omissions. What is not cultivated here is as telling as what is. A front garden is more than aesthetic; it is a sign of permanence, of emotional and material investment. Its absence suggests either constrained capacity or a deliberate withholding — a refusal, perhaps, to embellish what has never quite been one’s own.

These are not failures of design; they are signs of living within it.

The use of materials (brick, metal fencing, frosted glass) marks a desire for durability and control. But over time, residents modify these materials in ways that reflect personal needs: shielding from sun, creating privacy, securing space. These material modifications become biographical — not just what the houses are made of, but what they are becoming, through use and improvisation.

Viewed through Actor-Network Theory, the homes, fences, and appliances are not passive structures but active participants in daily life. They mediate temperature, security, privacy, and social meaning. The network includes not just the built environment, but the humans who maintain or adapt it, and the institutions who first installed it.

This is also a landscape of social stratification. These homes are not slums, but they signal economic marginality. The visual cues — patchwork repairs, deferred maintenance, lack of ornamentation — construct a spatial narrative of permanence mixed with precarity. In middle-class neighbourhoods, such signs might be temporary. Here, they are infrastructural. They speak of long-term adaptation without renewal.

Yet there is also agency. The fences, though utilitarian, diverge in colour, form, and upkeep. They delineate not only property lines but boundaries of identity and pride. Who maintains the front yard? Who repaints the gate? Who plants — or chooses not to plant — a garden? These are quiet performances of care, ownership, and autonomy — small acts of difference within a built landscape designed for sameness.

An anthropological reading of this scene reveals not architectural failure, but residents’ skill in making-do. Within a system built for efficiency, they generate meaning, comfort, and distinction. The houses do not merely shelter; they participate in the shaping of everyday life.

This is social housing not as policy, but as practice. A choreography of constraint and creativity. A standardised structure, remade from within.