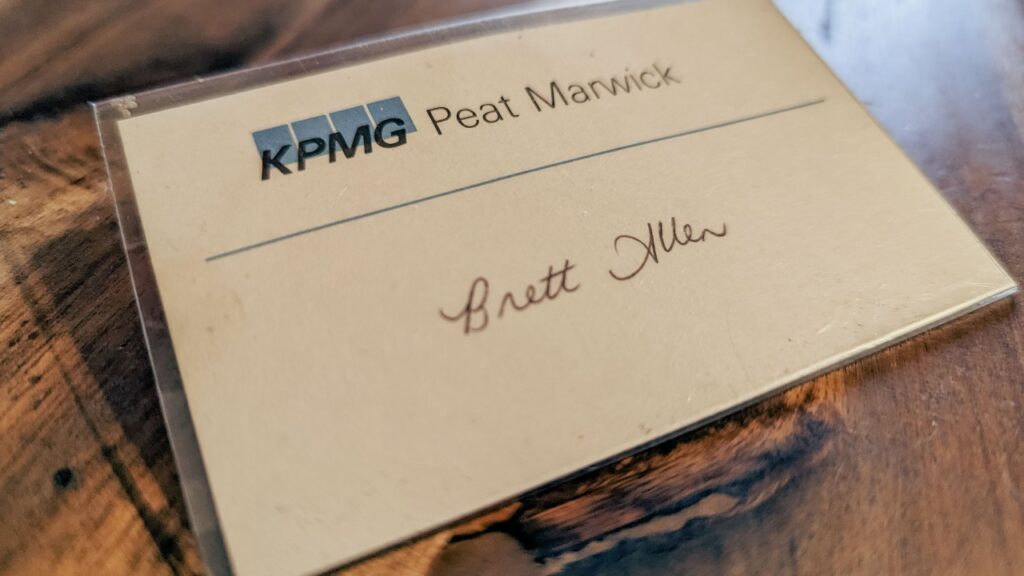

The emergence of a photo of a pen from a previous employer on Linkedin started me thinking about workplace artefacts (as you do). Then, going through an old portfolio, I found a name tag from my first full-time job at KPMG (Peat Marwick). In the diverse and intricate fabric of human culture and behaviour, our propensity for creating, using, and valuing material objects stands out as a compelling theme. This tendency extends beyond our personal lives, permeating into our professional existence.

Have you ever considered those artefacts from previous roles, whether a simple pen, a practical water bottle or a distinguished award, can carry embedded value transcending their immediate functionality? Anthropology emphasises human cultural variation, aiming to decipher the intricate relationships between individuals, societies, and their environment. Anthropologists such as Daniel Miller’s (Balthazar & Machado 2020) contributions have been instrumental in our understanding of material culture, underscoring how objects and consumption behaviours shape our world.

This subject could easily be a book; here are some quick thoughts.

Materiality and the Social Construction of Value

I have observed a fascination of anthropologists with objectification formulated by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1807). These concepts become more important in the neo-liberal capitalist era, especially to marketers. In his pioneering work The Social Life of Things (Appadurai 1986), Arjun Appadurai suggested that objects are deeply entangled with the social fabric, and their meanings are ceaselessly negotiated through social interactions. When applied to workplace artefacts, this concept illuminates how the value of a seemingly everyday pen or a drink bottle can dramatically escalate based on the social and cultural context they signify. Grab one of your artefacts and unravel all the memories and connections with this point in mind.

Objects as Cultural Texts and Symbols of Identity

These objects often serve as “cultural texts” bearing complex social and professional meanings. Clifford Geertz (1973) suggested that cultural phenomena can be interpreted as texts, extending to artefacts from previous roles. For instance, a lanyard from a tech conference could indicate one’s technical prowess, professional networks, and status within the tech community. Moreover, these artefacts often contribute to the formation of our professional identities. Symbolic interactionism, from a sociological perspective, posits that people act towards things based on the meanings they hold. Blumer (1969) argues that workplace artefacts are not merely physical entities; they are instilled with symbolic value that helps construct and reinforce our identities.

Artefacts as Cultural Capital

A favourite concept of mine was coined by Pierre Bourdieu (1986). Cultural capital refers to the non-financial assets that enable social mobility. In the form of objectified cultural capital, workplace artefacts represent more than physical objects. They are potent symbols of professional history and reputation, particularly when associated with prestigious institutions1.

An ID badge from a renowned company, such as KPMG, Google or Facebook, carries the prestige of that organisation, symbolising the individual’s connection to it. Even a pen or notebook can signal a link to power and prestige from a respected company.

These artefacts act as keepsakes and serve as status symbols, enhancing the holder’s social value and credibility. They mark the owner’s connection to a prestigious network, suggesting a competitive advantage in the stratified job market. Thus, keeping workplace artefacts becomes a social strategy, intertwining personal sentiments with broader social narratives and power dynamics.

Cross-Cultural Considerations and Place-making

Cultural variations significantly determine how much people retain items from their previous roles. Some cultures highly value the past and its artefacts, considering them ways to sustain connections with historical roots. In contrast, other cultures may prioritise the present or future, reducing the significance of workplace artefacts.

Lastly, workplace artefacts also play a crucial role in fostering a sense of place and belonging. Artefacts from previous roles can contribute to this sense of place, acting as physical anchors that connect us to past work environments and experiences (Low 2009).

Conclusion

These are only top-level thoughts. I may explore this further if I have time. We must consider complex cultural, social and psychological processes to understand why we hold onto artefacts from previous roles. These artefacts are not merely physical entities; they bear social and cultural significance, acting as ‘cultural texts’ that carry layered meanings.

Firstly, based on the contexts they represent, these objects contribute to the social construction of value. Objects that may seem ordinary or commonplace can take on a heightened value depending on the cultural and professional narrative they are part of, as Arjun Appadurai’s work suggested. This makes me wonder why so many “token” branded staff objects have little value and end up as landfill (sadly). So why do we hold onto certain items and not others?

Secondly, these artefacts often serve as potent symbols of our professional identities. The sociological perspective of symbolic interactionism emphasises that the meaning of objects is not intrinsic but socially constructed. These objects become ‘external symbols’ of our identities, helping form, affirm, and communicate our professional identities to ourselves and others.

Moreover, holding onto artefacts from prestigious or renowned companies can boost one’s cultural capital. These items act as symbols of recognition and status, carrying with them the prestige of the associated organisation and, by extension, enhancing the individual’s professional standing and social value.

Cross-cultural considerations play a significant role too. Different cultures imbue objects with varied significance levels, with some societies placing great value on artefacts as connections to the past. In contrast, others may prioritise the present or future, reducing workplace artefacts’ perceived importance.

Lastly, workplace artefacts also play a crucial role in fostering a sense of place and belonging. They act as physical anchors that connect us to our past work environments and experiences, providing a tangible link to our professional journey.

Cultural anthropology helps us understand the deep human tendency to seek continuity, identity, and significance in the material world surrounding us. This highlights seemingly ordinary workplace artefacts’ profound role in our lives.

I challenge you to grab an artefact from your draw and reflect on the importance of that employer in your career. These workplace experiences have helped make you the human you are today, better or for worse.

hashtag#anthropology hashtag#workplace hashtag#workplaceculture

References:

Appadurai A (1986). The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Balthazar A & Machado M (2020) ‘Material Culture And Mass Consumption: The Impact Of Daniel Miller’s Work In Brazil’, Sociologia e Antropologia, 10(3):773-803

Geertz C (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures. Basic Books.

Blumer H (1969) Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Prentice-Hall.

Bourdieu P (1986) ‘The forms of capital’. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, Greenwood.

Hegel G (1977) Phenomenology of spirit. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Low S (2009) Towards an Anthropological Theory of Space and Place. Semiotica